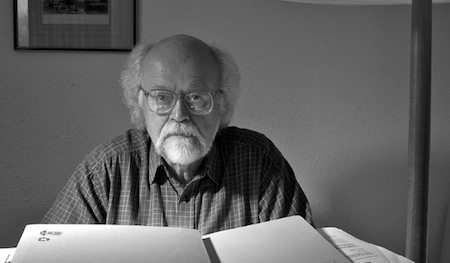

We would have lost a lot more of the diminishing architectural heritage of the East End if it wasn’t for the tireless campaigning of Tom Ridge. Tom Ridge is the man behind current attempts to preserve the industrial buildings of Fish Island and Hackney Wick from destruction by the developers. See our previous post .

It was Tom who discovered that an old building by the canal had been used by Dr Barnardo and was responsible for saving it, and creating the Ragged School Museum there – “because there should be a museum of the East End in the East End.” It was he who led the successful campaign to save the Bancroft Rd Local History Library when the Council would have preferred to close it down and sell off the collection. It was he who prevented buildings being constructed upon the small public park at the heart of Bethnal Green, by ensuring it was listed as of historic importance.

Find out more about him and his campaigns to save the East End’s architectural heritage in Spitalfields Life.

You can also find there “THE MODEST WONDERS OF HACKNEY WICK”, a series of photos recording the industrial heritage of The Wick.

I congratulate Tom Ridge and supporters in trying to save the closure of The London Chest Hospital Victoria Park. I worked there in the early 1960s. Here is an extract from my book 3: Near & Dear to Someone – out of the memoir quartet – Scenes from an Examined Life. publisher tredition.com

The Heart Surgeon.

It is not often that a man will cut his throat to save his life – but on my watch it actually happened. It was a very rare event for a patient to be admitted to The London Chest Hospital at night. It was on one of the foggiest nights of the year in December 1964, that an emergency happened, a couple of streets away from the hospital. Not a police officer, ambulance or doctor could get through. A member of an out-patient’s family rushed to the staffed Lodge by the hospital gate and related to the Night Porter that his father had cut his throat. The Night Sister was called down, and when she consulted with the duty House Officer, it was decided to admit the patient. Shortly after, he was carried in by a posse of his neighbours on a make-shift stretcher: a domestic internal door removed from it hinges. Carlton and I were alerted, given the patient’s name over the office phone and ordered to prepare for an admission. The Head Porter said something about a suicide bid.

As luck would have it, the patient was due for admission and his latest chest X-rays and clinical notes were on our ward. My co-nurse Carlton was panicking, but I said after we scanned the X-Rays that Mr. V. was showing a bi-lateral pleural effusion, so best set up for a chest aspiration procedure, adding that he is an old “trachy” case. I told her to go and check the ward steriliser and place a couple of T2s on steam while reminding her that we had looked after the patient twelve months previously. I described him. “You remember him?” As she went off she replied, “Oh yes: the man with the legs!”

The man with the legs was a 58 years old patient whose name was George Venables. He had been a docker, working in the London Docks Limehouse Basin area but was now disabled with chronic airways disease. During his last stay on the ward, he had to be relieved of chronic fluid retention in both legs. This was done with a series of minute needles set in the leg tissues and connected to fine tubes which gravity drained into two bowls at his feet. George had to be nursed sitting in an armchair propped with pillows in an upright position. He also had a silver tube inserted in his larynx – just below the Adam’s Apple – to assist breathing: in its opening a fine rubber tube could be inserted and eased down to allow frequent suction of lung secretions. After many weeks, George’s leg oedema was sufficiently reduced, and he was able to walk about. His tracheotomy was closed and he was discharged.

Sister Wise, the duty Night Sister, arrived and helped prepare a bed in a side ward and checked over Carlton‘s sterilised giving sets. She said Mr. Magdi Yacoub has been roused from on-call sleep, had seen the patient and decided not to summon the “crash” operating theatre team as he would treat the emergency on the ward with the aid of both medical and surgery duty colleagues. They brought Mr. Venables up in the lift. Sister Wise cleaned around the throat area and revealed the extent of the “throat cutting.” Through a neat opening, air hissed intermittently.

Mr. Yacoub began with “Thank you George – you have completed the first part of this operation perfectly – so the second part will not take long!” He then explained to all in attendance that the connective tissue over the previous tracheotomy had been neatly punctured. All that was needed now was to insert a tracheostomy. He did this in no time at all and secured the tube with fine tape slipped through the eyes of the flanges on each side of its protruding collar and tied at the nape of the patient‘s neck. A secondary removable tube was inserted into the primary tube.

Almost immediately, Mr. Venables was able to speak by placing a finger on the tracheostomy opening, and explain in short phases what had happened to provoke the emergency. At some point during the past couple of hours, he could not breathe and opened the back kitchen door of his house to get some fresh air. The dense “smog” almost overwhelmed him and gasping for air and sensing death, he got his wife to hold up a mirror and, reflecting the old tracheotomy scar in his throat, plunged a nail file into it. At once, he could breathe again.

Mr. Yacoub then explained to George that a principal cause of his shortness of breath was the fact that both his lungs were almost full of fluid. It would be necessary to perform a chest-aspiration straightaway. Mr. Venables agreed to this without demur – he had already experienced the procedure on several occasions. Mr. Yacoub marked the rib inter-costal sites and the Surgical House Officer drew off almost a pint of fluid from the base of each lung. Antibiotics were started and an hour later George’s face was pink in contrast to its earlier deep purple colour. Completely satisfied with his patient’s condition, Mr. Yacoub said: “I will come and see you again in the morning. Now I am going back to sleep. It is over to the nurses. George – you are a very brave man!”

As George became relaxed and drowsy, he asked me two questions: “Can I have a smoke?” and “Is Nurse Piano still on the staff?” The answer to the first question was: “Maybe in the morning after breakfast and to the second “Yes: she will be on duty to-morrow and will “special” you.

The son of a surgeon, Yacoub was born on 16 November 1935 in Bilbeis, Al Sharqia, Egypt to Coptic family[. He studied at Cairo University and qualified as a doctor with a Bachelor of Medicine, degree in 1957. He moved to Britain in 1962, and from 1964 to 1968 he was Senior Surgical Registrar, National Heart and Chest Hospitals, London.

Professional career

Moving to the United States in 1969 he became Instructor and then Assistant Professor at the University of Chicago. Returning to England, he became a consultant cardiothoracic surgeon at Harefield Hospital in 1973. From 1986 to 2006, he held the position of British Heart Foundation Professor of Cardiothoracic Surgery at the National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College Faculty of Medicine.

As a visiting professor to the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Yacoub, Fabian Udekwu, C. H Anyanwu, FRCS and others performed the first open heart surgery in Nigeria in 1974.

The Harefield Transplant Programme

Under Yacoub’s leadership, the Harefield Hospital transplant programme began in 1980. During this period there was an increase in post-operative survival rates, a reduction in the recovery periods spent in isolation and in the financial cost of each procedure. To remove donor hearts, he would travel thousands of miles each year in small aircraft or helicopters. Most of his patients received treatment under the National Health Service, but some private foreign patients were also treated.

In December 1983 Yacoub performed the UK’s first heart and lung transplant at Harefield.

He was appointed professor at the National Heart and Lung Institute in 1986, and was involved in the development of the techniques of heart and heart-lung transplantation.

Recent work

Having retired from performing surgery for the National Health Service in 2001 at the age of 65, Yacoub continues to act as a consultant and ambassador for the benefits of transplant surgery. He continues to operate on children through his charity, Chain of Hope.

In 2006 he briefly came out of retirement to advise on a complicated procedure which required removing a transplant heart from a patient whose own heart had recovered. The patient’s original heart had not been removed during transplant surgery nearly a decade earlier in the hope it might recover.

In April 2007, it was reported that a British medical research team led by Yacoub had grown part of a human heart valve from stem cells, a first.

Celebrity patients

Between August and October 1988 Greek Prime Minister Andreas Papandreou was hospitalized at Harefield, which he entered at a very critical condition, and Yacoub performed an open heart triple bypass surgery on the Prime Minister, saving his life. Yacoub has since become famous in Greece (Papandreou’s health problems and surgery were the top news stories in Greece for months), and Prime Minister Andreas Papandreou himself said that Yacoub saved him.

Among celebrities whose lives he extended was the comedian Eric Morecambe.He was also known to have treated the famous Egyptian actor Omar Sharif, urging the latter to give up the cigarettes that had led to his heart attack. In 2002, he was selected to head a government recruitment drive for overseas doctors. He has had a house named after him at The Petchey Academy which opened in September 2006. He established the Aswan Heart Centre in April 2009.

Yacoub’s 1980 patient, Derrick Morris, was Europe’s longest surviving heart transplant recipient at his death in July 2005. This record was superseded by John McCafferty who received a transplant at Harefield Hospital in Middlesex on 20 October 1982 in a procedure carried out by Yacoub and survived for more than 33 years, until 10 February 2016. He was recognised as the world’s longest surviving heart transplant patient by Guinness World Records in 2013,] surpassing the previous Guinness World Record of 30 years, 11 months and 10 days set by an American man who died in 2009.

My Name is Lesley Balding, Vice Chair of the Limehouse Community forum. We are organising a Social History Event and would to speak with Tom Ridge. Can you kindly put me in touch with him?

Yours assistance would be much appreciated

Many thanks

Lesley