Old Ford and Victoria Park stations have vanished along with most of the track from Bow Road. But the North London Railway (NLR) station, simply called Bow from 1850-1944, was reborn as Bow Church on the DLR in 1987. This railway line, and its history, are absolutely fascinating in many ways.

The Birth of the North London Railway

The London and Birmingham Railway opened in 1838. At Birmingham it joined the Grand Junction Railway which went to Manchester and Liverpool. This was the first intercity line to come into London. In 1846 the two parts merged to become the London and North West Railway – LNWR. This line linked many of the great and prosperous manufacturing towns to the most populous city in the world – London. Suddenly goods, businessmen, mail, and newspapers could be delivered on the same day. This must have turbocharged the economy.

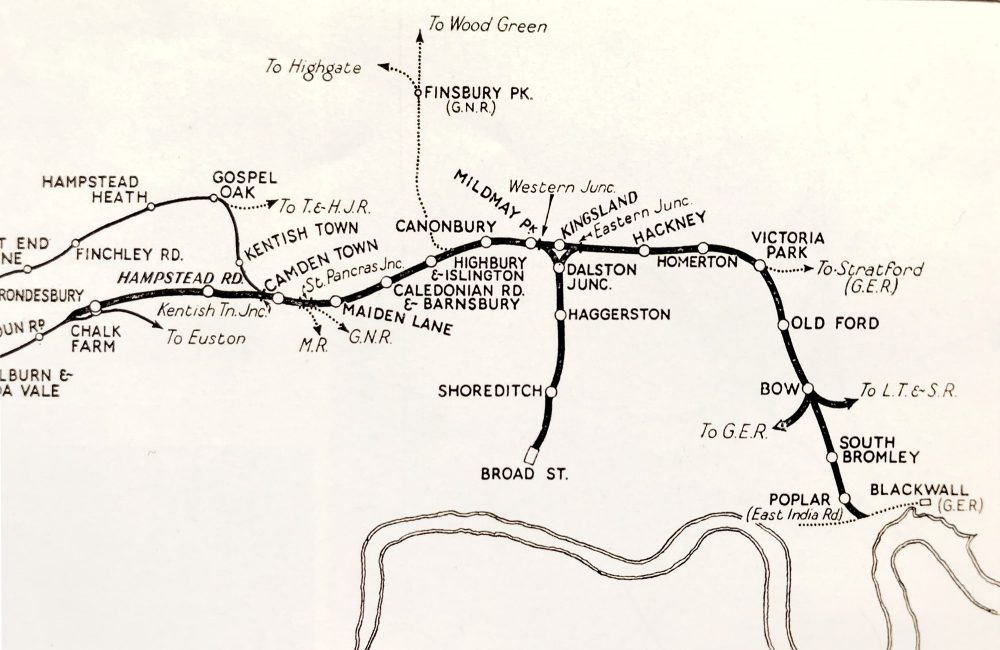

Railway mania developed at smartphone speed. In 1846 Fenchurch Street, London Bridge, Paddington, and Euston Stations were already operational, and others were under construction. The government decided that it would no longer grant permission for new lines terminating in London. What was required was a sort of ‘belt line’ to join some of these stations together. It was our local line, running up the east side of Bow, which got approved. It was originally called The East and West India Docks and Birmingham Junction Railway. Very grand, and commercially astute. At that time there were no goods lines reaching all those ships in London’s Docks. The line was up and running in 1851 and ran from Poplar though Bow, Hackney, Canonbury to Camden and Chalk Farm goods yard. Although only 8 miles long it enabled exports from Manchester and Birmingham to reach the West India Docks, and imports to go up the country. When the line got Royal Assent in 1846 it was intended for goods only. But when it opened it was soon carrying huge numbers of a new type of human – commuters. Right from the start it was company policy to run passenger trains at 15 minutes intervals.

Two thirds of the shares in the West India Docks and Birmingham Junction Railway were owned by the London and North West Railway. They urgently wanted to join their railway up to London’s docks and had money, experience, and the respected Robert Stephenson to help.

Poplar Dock

These being confident and ambitious times the company built its own dock, Poplar Dock, which also opened in 1851. A lot of coal arrived in London by sea. Our local railway, running north through Bow, facilitated the distribution of coal around London. Poplar Dock was the first in London to use hydraulic cranes. Being a “railway dock” it was always outside of the control of the PLA. The railway company was renamed as the North London Railway from 1st Jan 1853.

In Poplar Dock 73 cranes, 40 capstans, 8 coal wagon tippers, and a swing bridge were all run by hydraulic power which was supplied at an astonishing 700 p.s.i.

The NLR was good at collaborating with others. Freight trains worked by the London and North West Railway were running, just east of Victoria Park, down to Poplar as early as 1852. A spur off the track at Bow took the NLR into the city to Fenchurch Street Station. That station was built by the City and Blackwall Railway which ran a passenger service to Brunswick Pier at Blackwall. The NLR paid to use to Fenchurch Street, and was soon competing with the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway for access to platforms. In 1854 another spur line connected the NLR to Stratford from Victoria Park Station but was for goods only. Hackney Wick Station didn’t open until 1980. Although the NLR only owned 14 miles of track in 1900, it enjoyed 50 miles of running rights over other railways. In 1862 it was already running regular trains to Kew. The NLR also ran it’s own special excursion trains, for example, from Camden to Thames Haven (for steamships) and Southend.

Down at Poplar the NLR linked to Brunswick Pier near Blackwall. This was a steamer pier and in those early days huge numbers of passengers travelled down the Thames to Kent. They could set off from places such as Hampstead on the North London Railway and take a steamship from Brunswick Pier to Gravesend or Margate, and even across the Channel. Before the railways, in 1830, Gravesend Pier was already handling one million passengers a year. In January 1815 the paddle steamer Margery began running the “long ferry” route from Gravesend to London. In 1838 The Nautical Magazine and Naval Chronicle reported that a French steamer, the Phoenix, was running from Boulogne to London. Passenger transport was clearly going to be big business.

Broad Street Station

In 1860 the LNWR opened an amazing 6 mile long tunnel under the Hampstead Heights. The NLR was soon running trains though it. 1861 the North London Railway recorded 6.5 million passenger trips. With this kind of demand the board decided that they needed their own station in the City. In 1865 Broad Street Station opened, nine years before it’s neighbour – Liverpool Street. They’d closed Kingsland Station and created east and west branch lines heading south to a new station called Dalston (then on through the current Hoxton Station to Broad Street). This enabled passengers from all across north London (Hampstead, Crouch End, Haringey) to reach the City more quickly. Coming east around the corner of Victoria Park was the long way round. The result was an immediate doubling of passenger numbers on the NLR (14 million in 1866). By 1871 passenger numbers had doubled again.

Broad Street Station was expanded several times. By around 1900 it was handling about 800 train movements (in or out) each weekday. It had a goods lift down to warehouses underneath the platforms, maximising land usage. The station closed and was demolished in 1986. Trains were diverted elsewhere, especially to Liverpool street next door. The Broadgate office development now occupies the site.

Locomotive Building

William Adams was born in Limehouse in 1823. His father was engineer at the East and West India Docks Company. Young William Adams served his apprenticeship there. After gaining lots of experience elsewhere, he joined the NLR as the Locomotive Superintendent in 1854.

Initially the LNWR provided some engines by Stothert and Slaughter and from 1855 Robert Stephenson & Co were supplying engines.

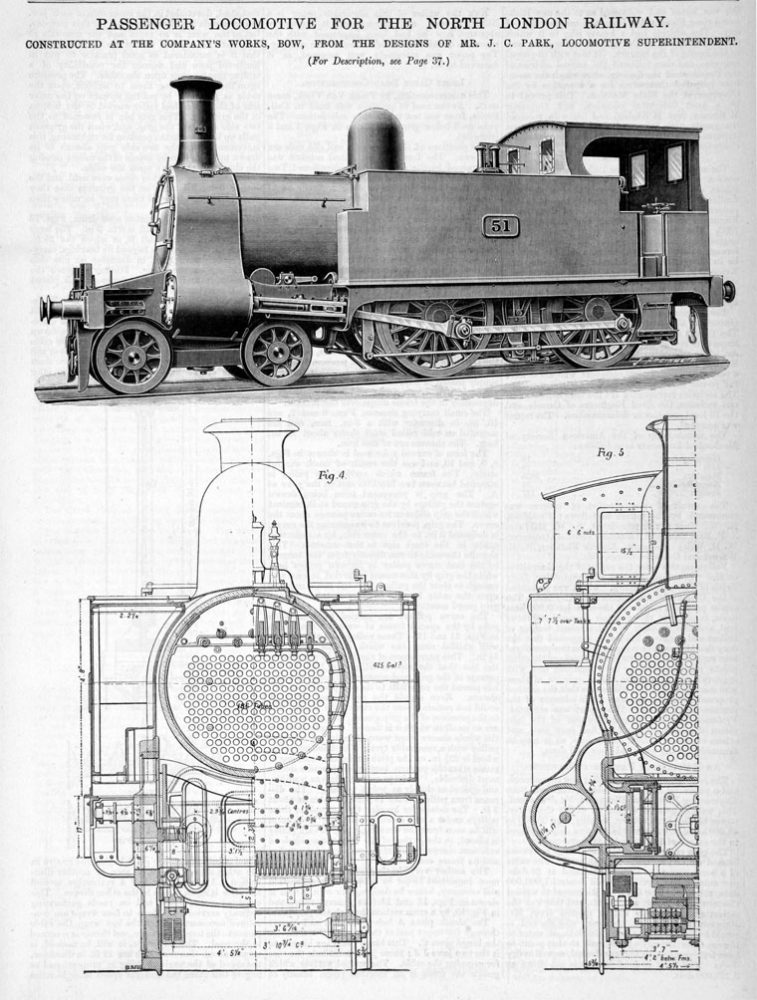

When William Adams joined he rapidly got the Bow Works up and running and the first engine he designed was built in 1863. The Bow Works was just south of Tower Hamlets Register Office, and is remembered in the street names: Rainhill, Stephenson and Trevithick.

The Adams engines had his patent bogie for the front four wheels. As well as rotating to go round curves, the Adams bogie could move sideways slightly against springs. This made for much smoother running on the tight curves of this suburban railway. These were higher pressured engines at 160psi, compared to others of their time. Thirty four of these excellent locomotives were built in Bow prior to 1876. By then all of the other many and various engines the company had bought were sold on. They’d standardised on this Adams design which was well suited to the short gaps between stations, and all the little gradients and curves necessitated by building a railway in a pre-existing city.

William Adams left in 1873 to take over running the huge Great Eastern Railway workshops at Stratford. He saved them a lot of money over the long term by introducing modern machinery and standardisation.

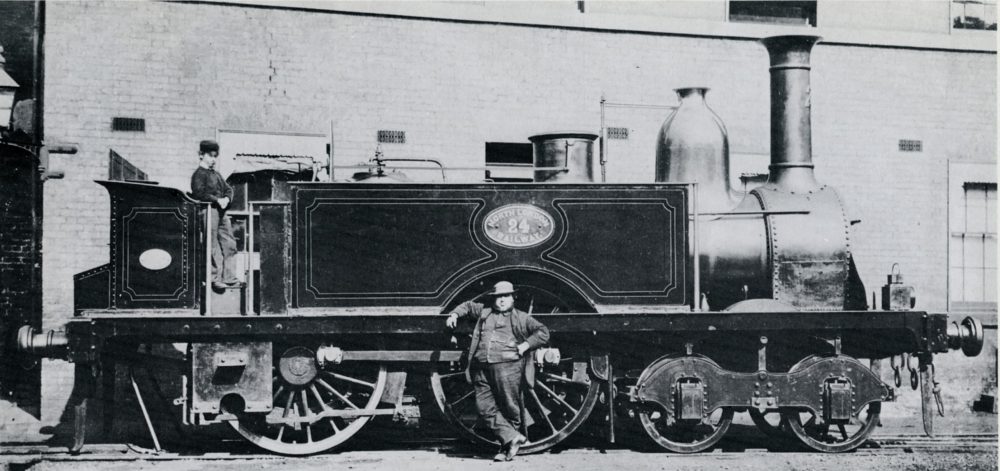

From 1876 (after William Adams had left) forty MkII Adams designed engines were built. As the earlier batch came into the workshops for their 15 year rebuilds they were upgraded to the new design. J. C. Park became the locomotive superintendent of the Bow Works from 1873 -1893.

J.C. Park designed the 0-6-0 freight engine above. Thirty were built from 1879. They were described at the time as “rough riding”, but they were remarkably efficient. During a test at Harlesden one of these engines pulled a train weighing 699 tons up a 1 in 100 slope (including the weight of the engine). Despite the daily bashing they got many were still in use in the 1950s.

From 1927 the Bow works started to repair locomotives that were running on the London Tilbury & Southend Railway. From 1930 Bow developed and manufactured an automatic train control system. After nationalisation in 1948 the Bow works developed the new BR automatic warning system, AWS. In 1956 Bow became the first all-diesel repair workshop. The works closed in Dec 1960. At its height the Bow Works employed 750 people. In 1909 the NLR owned 122 locomotives, 734 carriages and 568 wagons.

Workmen’s tickets and the first ticket machines

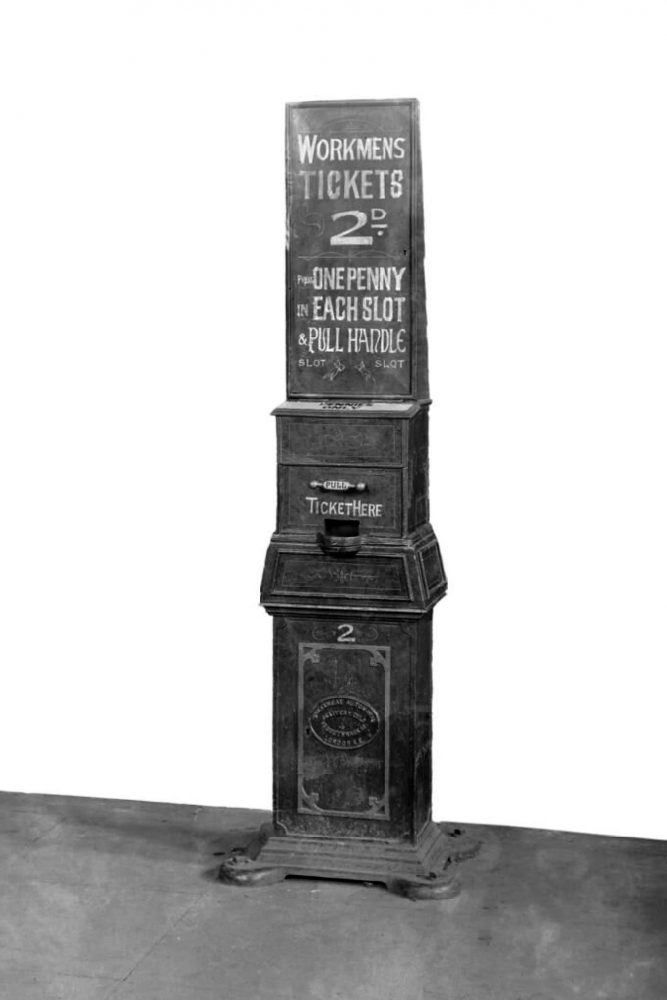

In the first half of Queen Victoria’s reign poor people walked to work. They had no choice. Knocking down slum housing to build mainline stations, and the tracks and viaducts leading to them, displaced thousands of people. These big infrastructure projects had to be approved by Acts of Parliament. Since the displaced people were going to have to live further out the Acts came with conditions. Special low priced workmen’s tickets had to be available.

The NLR built their business by running frequent services at low priced fares. Adams did away with having buffers at both ends of each car, they were only at one end. This maximised the carriage space available along the length of the platforms. The engines couldn’t carry much coal, forcing the drivers to economise. In 1853 the NLR achieved 4.37 million passenger journeys. The 1851 census gave Greater London’s population as 2.3 million.

The workmen’s tickets were only valid for a certain distance out of town. This changed the demographics of London. You’ll notice that the small Victorian and Edwardian terraced houses only extend so far. Later rehousing clauses started to be added to railway acts. You can see an example of that behind Bow Road tube station (1902). Wellington Buildings were built to house people displaced by the railway.

In 1898 the ticket machines like the one above were in use at Hackney, Homerton, Victoria Park, Old Ford and Bow stations. A penny in each slot bought a 3rd class return ticket between any two stations on the network. You had to get up early to use the workmen’s tickets. I believe these were the first automated railway ticket machines in the country.

First class passengers could buy annual season tickets for 10 guineas. They were valid anywhere across the NLRs own tracks. They came in a leather wallet embossed with the owners name in gold.

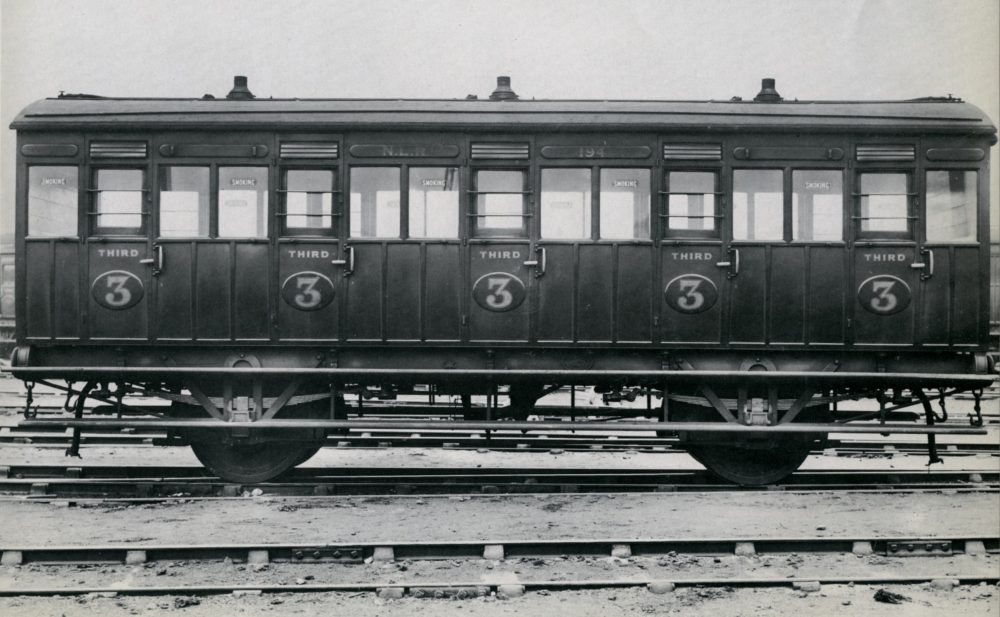

The NLR built all of its own rolling stock. The carriages were made of varnished teak and were built to last. Long after the NLR had sold them off they were to be found running on the Isle of Wight Railway and in many other places.

Decline

In 1896 the North London Railway achieved it’s best ever year. 46.3 million passenger journeys were recorded.

From the 1870s a multitude of horse drawn omnibuses were operating in London. You can see them in front of Broad Street station in one of the photos above. Soon horse drawn trams were adding to the competition. Two horses could pull 60 people smoothly along on recessed rails. The Whitechapel to Bow horse trams were licensed by Act of Parliament in 1870.

In 1903 the electric trams appeared. The bus garage in Fairfield Road was fully operational in 1909 as a tram depot. The electric trams offered halfpenny fares. The NLR was unable to compete at this price.

Then modern electric railways appeared. Hampstead station opened in 1907 with lifts which go down 180 feet. These are still the deepest of any London station. It’s now part of the Northern Line on the underground.

In 1913 the number of passengers carried by the North London Railway was less than half of the total for 1900. By 1921 it was less than a quarter. LNWR took over the NLR in 1922.

After the all-important Dalston Junction was bombed in 1944 the line through Bow closed to passengers for good.

In the 1970s the GLC persuaded British Rail to reintroduce services from Camden though a new station at Hackney Wick then on through Stratford, Canning Town, and Silvertown to North Woolwich. This was along old mid-Victorian tracks. I remember it as dirty and not very frequent. More recently a lot of the track built by the NLR became known as the North London Line. The section from Bow to Poplar was brought to life again for the DLR in 1987.

Hidden in plain sight

This article is long enough already. It provides an overview of the North London Railway. Have you ever wondered why there’s a hump at the eastern end of Tredegar Road?

Have you ever thought that the brickwork on the south side of the hump looked like the parapet of a bridge?

Walk into Pancras Way, opposite the parapet and turn right. Look over the railings behind the recycling bins and you’ll see where the trains used to run. All of the locomotives in the photos above would have regularly run under here. From Sept 1850 businessmen from the big houses in Hackney would have travelled south under Tredegar Road on their way to Fenchurch Street Station in the City. From 1852 machine tools manufactured in Birmingham would have passed under here heading for the docks. And long trains carrying coal would have dropped off wagons in sidings all the way to Camden.

Do any of our readers remember the trains running though here?

Alan Tucker

I can remember freight trains on the branch. The line split from the branch to Stratford above the Eastway tunnel where there was a signal box and then a bridge over what is now the northbound A12

Roger, thanks for the extra info.

The picture of NLR employees posing with an engine carrying a RICHMOND destination board was actually taken at the engine shed at South Acton, where NLR locomotives were stabled overnight, between working the last train of the day from Broad Street to Richmond and the first train of the day from there, to Broad Street. The shed was opened in 1880 by the North and South West Junction Railway, over which services were jointly worked by the NLR, Midland Railway and London & North Western Railway. The two-road building closed as a war emergency measure in 1916, never to reopen. It saw further use as a store until being blown down in a storm on 8th December 1954.

O:1880; C:1916; blown down 8/12/1954

I forgot where I got it now. It might have come from the London Metropolitan Archives.

Is the photo of the whole NLR train at the top of the article one of yours, or from the Science Museum Group? I would like to use it in my next book “The Rolling Stock of the Midland & Great Northern Joint Railway”. Some NLR carriages were purchased for use in Norfolk in 1884-5.

I lived on Morville Street, was very young at the time – probably 3 years old or so in 1980 when we moved there. Moved away around 84. We lived in a flat overlooking this railway line, and most of the time it was completely without trains! I was always waiting for something to come along, and I have a (hopefully true!) memory of seeing a train finally trundle through and into a tunnel. Which must have been a freight train, going by what you’ve said above. Good to know I didn’t imagine it!

Hi

My father in laws father had a scrap metal business in the 1940 / 50s in the LMS Bow Goods Yard East. His name was Clyde Albert Sinclair and the company was the East End Iron and Steel Company which I believe was in the vicinity of the Bryant and May match factory. Any details, pointers or pictures would be greatly appreciated

Bow 1940s. At the far end of Purdy Street in Bow, under the arch of the old Bow railway track {now DLR} was a circular island of terraced houses. I think the Purdy St arch was the only access to this unique little island.

I remember it devoid of people, knee deep in snow, no bomb damage. It stood on a piece of land adjoining Bow Locomotive Yard {now Rainhill Way}.

I wonder if perhaps only railways workers were housed there. Can anyone else remember it?

Jim, Thanks for your comments. This is fascinating.

I lived in Fairfoot Road and the train line at the back of my house took coal down to the gasworks in Cantrell Road. I would stand on the wall in my garden and watch the trains steam past. I told my Mum that I wanted to be an engine driver and when I was 21 I emigrated to Australia. Guess what I did in Oz for 40 years. Engine Driver. True story………………

Thanks for your comment Mandy. I’ll have a look.

It’s an interesting article and more in depth than the other articles I’ve so far managed to find but I still can’t find out on what date the Bow railway workshop was bombed and the resulting damage. All Wikipedia and other sites say is that it was during the Blitz and imply it was only hit once.

I would imagine that the site would’ve been quite busy considering the stress the railways would’ve been under to maintain services during the Blitz.

So my question is on what date was it bombed and if possible what time of day?

Many thanks for writing in, Roy.

My dad used to tell me that the first railway murder in the UK happened on one of these trains nearly a century before I was born. Because of where the body was found, behind and along from the old Top O’ The Morning pub, the murder was recorded as having been committed in Hackney. But my dad said that if you took a proper account of the time of the train and the direction of travel, the murder was actually committed in Bow. I also remember the Bow railway yards from when as a kid in the 1950s, with mates from Malmesbury School, we’d sometimes climb in and play in there.

Thanks Andy. This research can be never-ending. Being trapped in the house is a good time to work on it, although all the research libraries are shut.

Great Article. Really interesting, with time to read it in these coronavirus times!