Before WW2 Chrisp Street Market was a street of shops with market stalls along middle. A bit like the Roman Road Market looks today – but a lot more lively.

The background to the redevelopment of the Chrisp Street Market area

The demolition of much of Poplar was undertaken by German bombers in WW2.

During the war most of the able bodied men were away fighting, and there was a shortage of materials which persisted into the 1950s. Property which might have been restored was either neglected for too long, or pulled down anyway by the council. Nigel Henderson’s photos of Bow taken around 1950 show streets of terraced houses still standing where council flats were later built.

Hitler committed suicide on 30th April 1945. On the evening of 7th May BBC radio announced that the war in Europe was officially over, and that a Victory in Europe holiday would be held the next day. There was no time to prepare for it.

On the days around VE day the 2,000 diarists working for Mass-Observation complained of a lack of public information. Celebrations were spontaneously organised. Most diarists around the country reported that people were just hanging around – in contrast to the selective press photos we see today. But the street lights were lit for the first time in years, and buses were driving around with the interior lights on. Children were astonished by this. They didn’t know this was how towns were meant to look.

Mass-Observation was a social research project founded in 1937. Observers sat in pubs, travelled in buses, and visited homes, shops and factories recording what they saw and heard. In 1939 they published a popular book called Britain by Mass-Observation. In it Charles Madge and Tom Harrison say that they are finding out what the “Man or Woman in the Street” thinks, needs, feels, believes. At the time most of the population were voiceless. Newspaper barons and politicians made the decisions. In the book Tom Harrison said, “Anthropologists, who have spent years and travelled all over the world to study remote tribes, have contributed literally nothing to the anthropology of ourselves.” He’d studied anthropology at Cambridge. In 1945 a Mass-Observation observer moved into No. 46 Chisenhale Road, Bow.

There were no plans made during WW1 for what should happen after the war was won. The returning troops had hoped to come home to a better world. But it wasn’t. The Housing Act of 1919 permitted housing to be built by the London County Council outside it’s own area. In 1921 the first “Homes for Heroes” were ready for occupation on the Becontree Estate. A while ago I made a little pilgrimage with a camera to photograph them.

Recovering from WW2

In 1942, in the midst of WW2, ‘The Beveridge Report’ (officially called Social Insurance and Allied Services) was published. William Beveridge said it was to address what he identified as “five giants on the road of reconstruction: Want… Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness”. In 1945 the incoming Labour Government started implementing it, including establishing our National Health Service. One of their manifesto pledges was for an urgent housing programme.

The New Towns Act of 1946 set out to relocate residents of bombed out or poor housing to new areas. Around London the first under the act were Basildon, Bracknell, Crawley, Harlow, Hatfield, Hemel Hempstead, Stevenage, and Welwyn Garden City. Of course a lot of people didn’t want to move. Planners probably didn’t know how important informal support networks of sisters, cousins, grandparents, aunts and friends were to working people bringing up children. New towns did offer the popular two storey houses with gardens. They were an extension of The Garden City Movement.

Festival of Britain – 1951

Ideas had been mooted for holding a trade exhibition on the centenary of the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations held in 1851. It had been held in a huge ‘Crystal Palace’ in Hyde Park. It was enormously successful in promoting trade around the world. Thanks to the new railways, six million people visited, a third of the population. The exhibition made a profit, and funded the museums along Exhibition Road in South Kensington.

After WW2 Herbert Morrison the Deputy Prime Minister, and former leader of the London County Council took charge of the 1951 project, and named it ‘Festival of Britain’.This was not to be an international trade fair, but focussed on British achievements. It promoted British science, technology, industrial design, architecture and the arts. It was to show the public that we had turned the corner from the devastation of war. This was a much better organised celebration than VE Day. It ran from May to September. The future was bright, in strong primary colours and new materials – formica, nylon, pyrex. It helped reshape Britain’s arts, crafts and design industry creating a contemporary style.

The public was very well aware that wartime restrictions were continuing. The bright future hadn’t arrived yet, but there was a sense of optimism in the air. Despite the new furniture designs on display, the Utility Furniture Scheme, designed by the government to cope with raw material shortages during the war, continued until 1952 when furniture rationing ceased.

The 1951 exhibition was also a success, and turned a small profit. It had plenty of seating for people to relax, and good quality, reasonably priced cafeterias. It provided a positive, reassuring message that people wanted to hear.

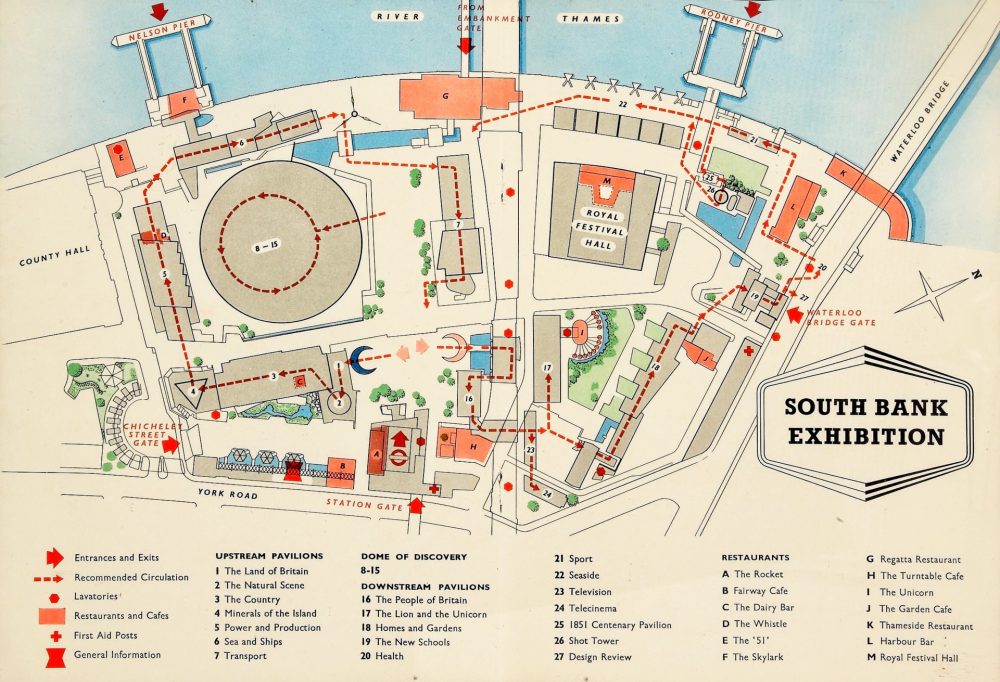

The main exhibition was on the South Bank of the Thames near Waterloo Station, but celebrations and displays took place across Britain. The Royal Festival Hall is still in use, and mementoes of the festival are still to be found, as shown in my photos below.

Chrisp Street Market and Lansbury Estate Poplar

There were plans to include an Exhibition of Architecture on the South Bank festival site. But respected architect Frederick Gibberd suggested that instead they could put on an exhibition of Live Architecture. He said that a bomb site could be developed to show a real piece of London being rebuilt. Chrisp Street Market was the chosen site. It was named the Lansbury Estate after the former Mayor of Poplar and 1930s Labour Party leader. It was Gibberd’s idea that the something permanent should remain after the festival was over. Seventy years later it’s still there.

Frederick Gibberd had a good reputation for designing flats. In 1937 he wrote a book called “The Modern Flat”. He was the Principal of the Architectural Association and in 1947 had been appointed as the planner for Harlow New Town. He then lived in Harlow until his death in 1984.

The Lansbury Estate was developed as a neighbourhood to function like a small town. It included everything people would need to live fulfilled lives – a school, shops, pubs, a church, a library etc. Chrisp Street was England’s first modern pedestrianised shopping precinct.

In the 1930s Gibberd became a member of the Modern Architectural Research Group (MARS). It contained some uncompromising modernists. Gibberd became a soft modernist in the 1940s, trying to create an English style with a pleasing look, an emphasis on traditional materials, and considering the total environment.

Other architects were very critical of the Lansbury Estate and it’s new Market Square. Some had been to see Le Corbusier’s first Unité d’Habitation at Marseille which was completed at about the same time. This is what they dreamt of doing.

Le Corbusier built a series of Unité d’Habitations. They look beautiful and well-maintained. Unfortunately most of the British architects and who were inspired by him seem to have failed spectacularly.

Judith and Nigel Henderson move to 46 Chisenhale Road in 1945

The short answer to who they were is impoverished, but well-connected Bloomsberries.

Nigel had piloted planes for Coastal Command seeking out and destroying U-boats and protecting shipping from the Luftwaffe. A stressful job. After the war he had a nervous breakdown. His wife Judith was Virginia Woolf’s niece.

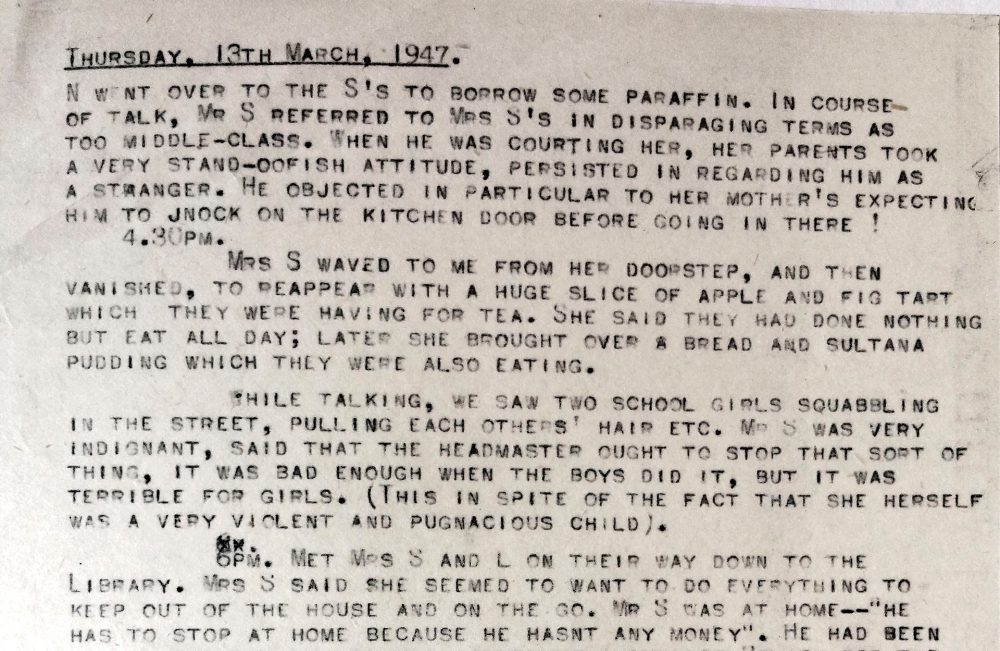

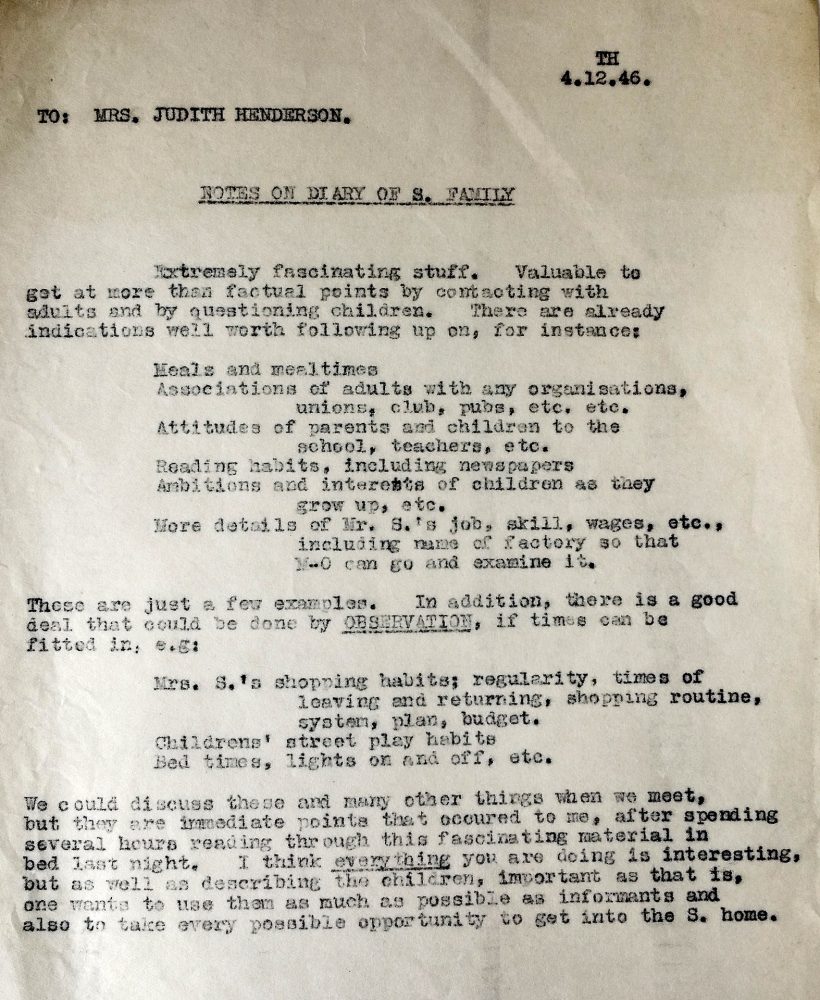

Judith Stephen was very bright and had studied economics and anthology at Cambridge. They moved to Bow as a condition of her work for an offshoot of Mass-Observation called ‘Discover Your Neighbour’. Her job was to secretly gather detailed information about the behaviour of the local working class community. She spied on her neighbours and typed up a diary of what she found out. The Hendersons were upper-class intellectuals studying the alien life forms they found in the East End. Nigel said it was like watching live theatre, “My neighbours appeared to be living out their lives in response to some pre-determined script.”

I went to the Mass-Observation archive and photographed some of Judith Henderson’s reports.

In the above report Nigel Henderson might have used borrowing paraffin as an excuse to get inside the Samuels house. He came home with confidences Mr and Mrs Samuels had said about each other. His wife typed it up to post to Mass-Observation. This is madness!

Around this time Nigel Henderson took up photography and walked the local streets with a camera recording what he saw. He had gained a serviceman’s grant to study art at the Slade

Nigel Henderson had many artistic friends. The photo below shows four of them posing as trendy kitchen sink social realists. It was taken for the catalogue of the “This is Tomorrow” exhibition at Whitechapel Art Gallery 1956.

The Villains of Brutalism in Poplar

Two of the villains are in the photo above. Alison and Peter Smithson were the architects of the brutalist Robin Hood Gardens, a short walk from Chrisp Street. They were admirers of Le Corbusier. His 20 storey Unité d’Habitation at Marseille was built to house 1,600 dockworkers and their families. They wanted to launch their careers by designing something similar on a grand scale. But wasn’t until the late 1960s that they designed Robin Hood Gardens, below, for the Greater London Council (GLC).

The Smithsons spent a lot of the time with the Hendersons. They would accompany Nigel on his walks with a camera. They wrote about the benefits of going out with him. He showed them the self-sufficiency of the local community surviving in difficult circumstances. They studied the detail of daily life and the social cohesion. The Smithsons would have also have had access to Judith’s Mass-Observation reports. This led them realise the importance of the street and the community when building social housing. “streets in the sky” was one of their slogans. The “streets” are the horizontal lines every few floors in my photo above. There were wide enough so that two people could push prams past each other and maybe stop for a conversation – as they’d seen in Chisenhale Road. But the East End’s rich street life was never going to thrive halfway up an ugly slab block. The “streets” didn’t link the two blocks together, nor did they connect to the ground. The Smithsons thought that they could build a series of massive “landcastles” across the East End. Instead Robin Hood Gardens effectively finished their careers.

In 1952 for their failed bid to design the Golden Lane Estate they were talking about joining blocks with wide pedestrian decks called “streets-in-the-air”. They said the refuse chute would take the place of the village pump. The next year they got to present at the 9th Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM). They showed montages of famous people walking along “streets-in-the-air” and Nigel Henderson’s photos of children’s parties held in the middle of Chisenhale Road for the Queen’s Coronation. This is how they thought people would use the wider decks of blocks of flats.

Nigel Henderson was able to photograph children playing in Chisenhale Road because it’s a backwater, not a main road. In the 1950s hardly anybody could afford a car. Petrol rationing lasted until May 1950. Cars were exported to pay off the national debt. If you were a doctor you went to the top of the list. Most other people had to wait years. But planners started to see that the roads might soon become choked with new cars, so they devised schemes to separate pedestrians from the traffic. The 1962 Highwalk over London Wall and around the Barbican is one example. People were totally confused by them. A planned city-wide scheme was never built.

By 1955 the London County Council (LCC) had come round to the idea of hard modernism. They had rejected Gibberd’s more humanist approach at Lansbury. Building giant blocks of flats enabled greater housing density inside London. Further away, outside the green belt, people could have the type of houses they wanted. Inside London working-class people were going to have to put up with what they were offered.

The Smithsons made a lot of self-promotional noise and got a lot of coverage in the architectural press. They blathered on about “le Béton brut” the raw concrete used by Le Corbusier at Marseilles. This was picked up by the architectural historian, Reyner Banham, who coined the phrase New Brutalism which quickly became a derogatory description.

Robin Hood Gardens consisted of two huge blocks with some green space between them. It was complete in 1972 and contained 213 flats. The site is surrounded by noisy main roads, so a concrete sound barrier was built around it.

As well as the “Berlin Wall” the blocks were surrounded by a “moated” car park to further enhance the feeling that people were living inside a giant prison.

But the idea that these buildings contained “streets in the sky” meant that anybody could walk in – and did. The walkways were dead ends and the enclosed stairwells had blind spots. Ideal or drug dealers and muggers. It soon gained a reputation as a poorly maintained, dangerous, “sink estate”. It was plagued by vandalism which the Smithsons blamed on the tenants. Years later when an entry phone system was put in the problems stopped. They were caused by a handful of outsiders coming in.

A heap of rubble from the previous Grosvenor Buildings was piled up in the middle of the central garden a grassed over to create a hill. This was deliberately done to prevent children from playing football and creating a noise. At every stage it looks like the wrong decisions were made. The Smithsons said that the flats were built using robust concrete so that the building’s lower-class, and often criminal occupants would be less able to damage it.

I hope the video below of the Smithsons, made whilst Robin Hood Gardens was under construction, stays available. They reveal themselves as miserable crazies spouting surreal sentences laced with their slogans and bizarre statements. A comment by Sciflyer Nineteensixtynine says: “You see why this project failed simply by listening to the Smithsons, condescending and egotistical, essentially espousing that they were doing society a favour by creating this monster and that they feared it might not be appreciated.”

Eventually Tower Hamlets Council decided to demolish Robin Hood Gardens. In 2008 there was a backlash from big name architects. Richard Rogers said: “The building’s original concept combined heroic scale with beautiful, human proportions.” What rubbish. Robin Hood Gardens is being demolished and replaced with a new mixed income housing scheme.

Goldfinger: Bond Villain and Brutalist Villain

Ernö Goldfinger was born in Budapest. He studied in Paris from 1923 where got to know Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe and many other architects. He was Jewish and wisely moved to London in 1934. He and his wealthy wife, Ursula Blackwell, moved into Highpoint I, by Berthold Lubetkin, who he already knew. It was a new, stylish modernist, building at the highest point of Highgate. To promote his architectural practice he decided to demolish a picturesque row of cottages overlooking Hampstead Heath and build a modern row of flats, including a showcase for himself. This sparked a big row with the Hampstead hierarchy, including his near neighbour, Ian Fleming. Later, when working on his seventh James Bond book, Fleming decided to name his villain Auric Goldfinger. Having no sense of humour, and a big ego, Ernö Goldfinger sued – to no avail.

The flat Goldfinger built for himself at 2 Willow Road looks innocuous by today’s standards. It’s owned by the National Trust so you can visit it. On the top floor there were bedrooms for a nanny and two children. But the walls were made of folding screens so the whole area could be opened up to create a children’s play area during the day. The chauffeur and a cook lived in the basement. Food was sent up in a dumb waiter. You can see how qualified he was to be building social housing.

Unlike the Smithsons Goldfinger managed to get plenty of commissions. Below is his 1946 offices and print works for the Daily Worker at 75 Farringdon Road. I remember it, as I was working in Clerkenwell in the 1980s. It was ugly, and decrepit. It was demolished in 1988.

In 1959 he won the commission to reconstruct five sites at the Elephant & Castle. The Elephant is an important gateway into London from the south. What Goldfinger designed was grim and awful.

In 1963 he was commissioned By The LCC to design the 26 storey Balfron Tower, on the Brownfield Estate alongside Frederick Gibberd’s Chrisp Street Market and shops. It contains 136 flats and 10 maisonettes.

The lift shaft was separated from the tower, not as I’d originally thought for fire safety, but to insulate the flats from the sound of the lift. The lift only stopped at every third floor, hence the layout of the walkways.

During WW2 Poplar Borough Council had a team of 1,500 men conducting emergency “first-aid” repairs to bombed houses. In 1944 it started building 23 ft x 19 ft huts as temporary accommodation, and in 1945 the first prefabs started to be delivered. By the 1960s the council was under pressure from the government to hurry up supplying housing and to build high-rise.

After Balfron Tower was complete in 1968 Goldfinger moved into one of the flats temporarily and hosted champagne parties for residents to learn what they liked and disliked. He then made adjustments to Balfron’s twin – Trellick Tower in Kensal Green, which opened in 1972. Trellick Tower immediately became a magnet for crime, vandalism, drug abuse and prostitution. Residents wanted to move out. In the 1980s security measures were put in place, a concierge employed, and the situation improved.

Trellick Tower was the last major project Goldfinger worked on. He too managed to trash his own reputation by designing Brutalist public housing.

Goldfinger also built Carradale House, below, which is 11 storey and contains 88 flats. It was completed in 1970. It’s next to Balfron Tower.

In 2007, following a ballot of residents, Tower Hamlets Council transferred the ownership of Balfron and Carradale to Poplar HARCA housing association. They are both Grade II listed! Partway through restoring the buildings all the residents were decanted, then in 2015 it was announced that no social housing would be retained, and that all the flats would be sold. They had been built as council housing.

Brutalism has now become retro chic.

Loose Ends

In 1954 Judith Henderson inherited a pub and some cottages near Clacton. They left Chisenhale Road to live there. Nigel became a part-time college lecturer, and in the 1970s one of my friends went on one of his photography courses, and was influenced by him.

Mass-Observation continued until the 1960s. It was revived in 1981 by Sussex University who hold the archive. Beware of any new friends asking too many questions!

Urban Splash have gained a good reputation for turning around housing which other people have given up on. They’ve revived the Brutalist Park Hill estate in Sheffield.

I used to visit Leeds Photographic in the Brunswick Centre in the 1980s. They sold and hired out professional photographic equipment. It was a dark, dirty Brutalist shopping centre, built in 1972. Lots of shops were empty. The flats above became a social housing ghetto. It turns out that the concrete was always supposed to be painted blue and cream. In 2006 it was restored to how it was designed, and together with some improvements now looks very good.

Alan Tucker, Bow

My family are from Chisenhale Road from the 1st world War up until the 1960s.

Judith Henderson appears self-righteous and judgemental. What kind of person makes ‘friends’ with neighbours only to ‘observe’ and pass comment on their behaviour and habits.

Thanks Carolyn

Thanks for intriguing post Alan. I understand the Samuels were not aware they were being ‘observed’ and were angry when they found out, but the friendship carried on. For those interested, the Festival of Britain Society has a Facebook page: Festival of Britain (1951) Society