Photos from the 1930s to 50s by Edith Tudor-Hart and her brother Wolfgang Suschitzky are on free display in the Spotlight Gallery at Tate Britain until 17th Nov 2019. It’s a big square room, and there are a lot of photographs. Most of the prints have been recently made from the original negatives. It’s great to see the sheer quality of these prints. Prior to my visit I had only ever seen these pictures as reproductions.

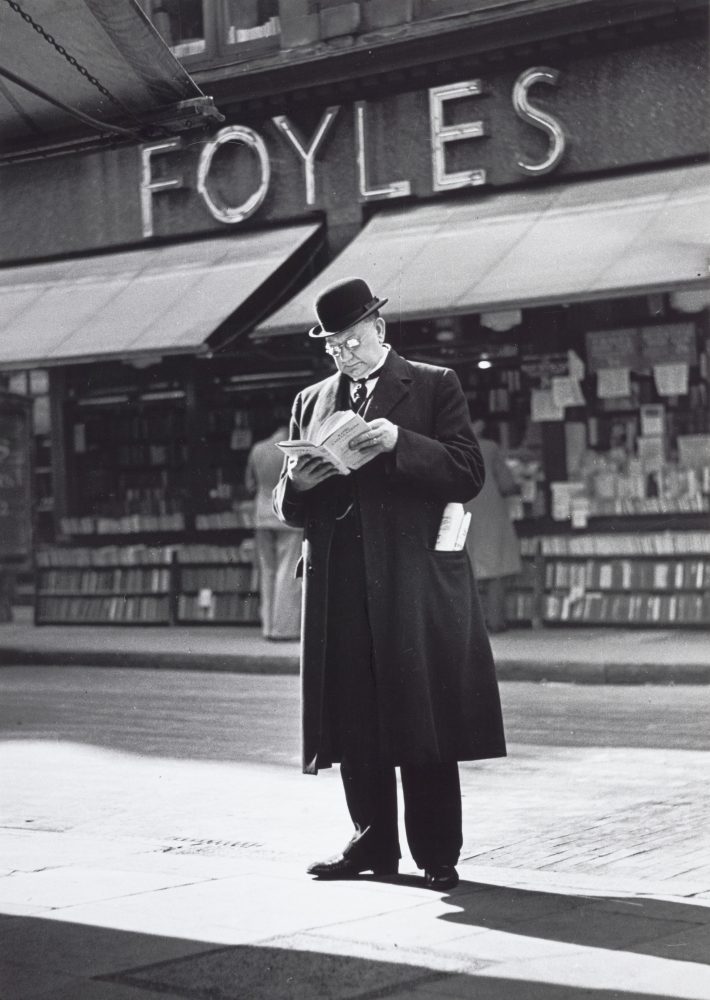

I’ve been seeing photos credited to Edith Tudor-Hart, and sometimes as Edith Suschitzky, crop up in magazines and photo annuals since the 1960s. I always appreciated her vision and technically adroit handling of light. The photo below would not have been easy to take with the equipment and film available in the 1930s.

Gradually I learned more about her background and saw the odd mention that the security services were keeping an eye on her. It’s only more recently that declassified documents revealed that Edith Tudor-Hart was a Soviet agent.

The Tate exhibition concentrates on more on Edith’s socially aware photography. But she was taking photographs only in the service of her political beliefs. When it came out that his sister was working for Stalin’s Russia, Wolfgang said he was surprised, and dismissed a story in the Daily Express as a prank. Nigel West was granted access to the KGB archives during Glasnost, after Mikhail Gorbachev came to power. He’s seen the evidence that, of course, Wolfgang knew; although he wasn’t involved. Wolfgang Suschitzky (1912 – 2016) was a 1930s documentary photographer of such skill that he became a cinematographer.

You can see some of his 1930s East End of London photos on the Tate website here.

Edith Suschitzky was born in Vienna in 1908. Her parents owned a left wing bookshop and also printed and published socialist books. In 1924 she was working as an unpaid teacher in a nursery school run as a collective. Teachers were trained, and since she showed promise, 16 year-old Edith was sent to London for a three month course with Maria Montessori. Her political ideology stems from the Jewish radicals she met at this time. And also from seeing the terrible conditions working class people endured in the aftermath of WWI.

The 1929 Wall Street Crash was a huge worldwide crisis caused by unfettered capitalism. The European liberal intelligentsia looked to the new communism for a better, more moral way. They hadn’t noticed the dark side of the murderous Bolsheviks. To bring about collectivisation wealthy peasants were deprived of their land. Stalin announced the “liquidation of the kulaks as a class” on 27 December 1929. About 5 million people were killed between 1929 – 33. This brought about a great famine which killed another 2.4 to 4 million people.

With local Fascism on the rise, Edith Suschitzky chose Communism.

Back in Vienna, at the age of 17, she fell in love with Arnold Deutsch who was an agent for the Comintern – Communist International, founded by Lenin in 1919.

It’s known that she was working for the CPGB (Communist Party of Great Britain) in 1927. She was already a member of a similar Austrian organisation called the KPÖ, and was thought to be working for the OGPU, the Soviet Secret Police, whilst still in Vienna.

In 1929 the Comintern asked Deutsch to go to Russia, and as a leaving present he gave Edith a very early Rolleiflex camera. The bigger sized negatives that the Rolleiflex took enabled it to take better quality photos than the Leica. You’ll notice this if you visit the exhibition. Edith gave up her job as a kindergarten teacher and went to the Bauhaus to study photography. It was here she gained a great technical education in photography. The communist students at the Bauhaus even published their own magazine.

In Vienna Edith would have seen great artistic photographs in the modern style. There was also a worker photographer movement underway which issued guidance as to what to photograph and how. It didn’t work as well as everybody hoped. Austrian magazines complained about the photographs they were being sent. One said, “Our worker photographers have failed as photojournalists to the extent that the were incapable of capturing momentary situations.” What they were getting at was that they didn’t want nice landscapes, nor did they want pictures of staged demonstrations. What they wanted was clandestinely taken photos in factories, the workshop and the labour exchange, families fighting eviction.

In 1930 Edith came back to London to meet Alexander Tudor-Hart, a married doctor who later became her husband. Her political activities and choice of friends soon brought her to the attention of Special Branch. She was expelled from the country.

Back in Vienna she was hired by TASS, the Soviet news agency, as their Austrian photographer and correspondent.

In Spring 1933 the Austrian Parliament was abolished, politics went far right, and 800 communists were rounded up. Edith Suschitzsky was caught redhanded working as a courier for the communists, and was found to have a treasure trove of incriminating documents and photographs at home. Whilst in prison, awaiting trail, Edith was allowed out marry Alexander Tudor-Hart in the British Embassy. At the same time her friend Litzi Friedman married Kim Philby in the Embassy. Since both Edith and Litzi became British subjects by marriage they were allowed to accompany their husbands to London. Edith never returned to Vienna. Most of her archive of photographs had been confiscated and destroyed.

Arnold Deutsch (illegal agent, codename OTTO) was sent to London to recruit new agents to work for the Russians. In 1934 Edith, in classic spy style, introduced Kim Philby to Deutsch, who was sitting on a bench in Regents Park. Nigel West explained how the system worked:

- Talent spotting

- Cultivation

- The access agent (Edith) creates “the bump” – an accidental meeting

- The pitch was made by Arnold Deutsch

Kim Philby agreed to try to get himself a job working for British Intelligence. Bit by bit all of the Cambridge spies manoeuvred themselves into positions where they were trusted to handle highly sensitive and top secret information. At one point Guy Burgess asked the Soviet Embassy in London to buy a suitcase because he had so many documents to give to them. He would regularly hand over a briefcase full of documents, which they would copy and return to him later.

When Deutsch was recalled to Moscow Edith Tudor-Hart became the lynchpin of the Soviet network in Britain. The “Cambridge spies” – there was a lot more than five of them, changed history and remained undetected for decades.

During WW2 John Cairncross used to walk out of Bletchley Park with his trousers stuffed with decoded messages from the German high command. He’d take them down on the train to London to give to his Soviet handler. Simultaneously Churchill was feeding Stalin selected decrypts to help him win against Hitler. The Soviets couldn’t believe the quantity and ease with which they were getting top secret intelligence. They thought they were being set up by the British.

Philby identified every single intelligence officer to the Russians, writing personality profiles for each of them.

Anthony Blunt walked into the secret archives and took out every single document relating to Soviet espionage.

Engelbert Broda worked at Britain’s Cavendish nuclear laboratory. He passed thousands of pages of top secret documents about British and American atomic research to Moscow. Stalin tested Russia’s first atomic bomb in 1949. At that time Edith Tudor-Hart was Broda’s lover.

In 1951 Donald Maclean and Guy Burgess defected to the Soviet Union.

Edith Tudor-Hart was interrogated in 1952 by MI5 about what she knew about Kim Philby. The file says: “This woman steadily prevaricated from one end of the interview to the other…” She destroyed much of her photographic archive around that time as it could have incriminated many people. MI5 stopped her working as a photojournalist for security reasons.

Philby did not defect until 1963. Protected by his friends in MI6, he became a correspondent for the Economist and for the Observer.

When Anthony Blunt confessed in 1964 he said of Edith, “She’s the grandmother to us all.” MI5 suddenly panicked because they didn’t know where she was. It turns out that she was running an antiques shop at 19 Bond Street, Brighton. She lived above the shop.

It’s not believed she made any money from her spying activities, and was always hard up, sometimes having to pawn her typewriter. She was doing it purely for ideological reasons – but so were the others, and they were getting paid by results. Burgess, for example, was given both a monthly income, and occasional bonuses of £250 during WW2. He was also getting paid by the BBC, for producing talk shows on current affairs, and by the Foreign Office.

Edith Tudor-Hart died penniless at Brighton in 1973, aged 64. Her brother Wolfgang said, “My sister had a hard life.” Her son Tommy was born in 1936. He was fine until about the age of five when it became clear that something was wrong. After he was eleven he spent the rest of his life in mental institutions. The year that Tommy was born, Alexander Tudor-Hart left to run a republican medical unit during the Spanish Civil War. The marriage was over. Edith was now a single mother trying to work as a photographer whilst being constantly watched and followed. Her flat was regularly searched by the security services and her post was intercepted.

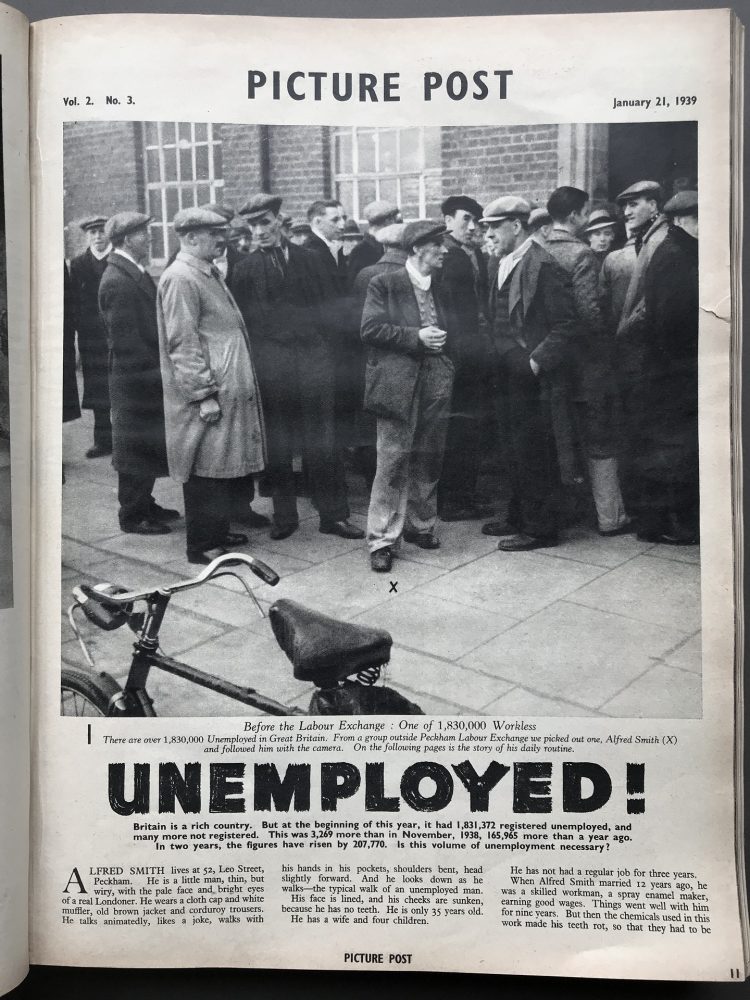

Before television took over in the1950s, picture magazines provided in-depth analysis, and great photojournalism to show the public current topics. By 1939 the British weekly, Picture Post magazine had sales of 1.7 million, and was reaching a readership of many more.

The photo above shows the opening page of a 9-page story about unemployment. The article says: “Britain is a rich country. But at the beginning of this year, it had 1,831,372 registered unemployed and many more not registered.”

The journalist and the photographer followed a Mr Alfred Smith of 52, Leo Street Peckham. He had a wife and four children to support, and had not had a regular job for three years. “When Alfred Smith married 12 years ago, he was a skilled workman, a spray enamel maker, earning good wages.” The article features 17 photos. They are not credited, but one of them I know is by Bert Hardy, so I assume the rest are his too. Week in, week out, Bert Hardy (and others) reliably produced long form photo stories to order.

I mention Picture Post magazine because it reached a heck of a lot of people of people. This was the first of a series of hard-hitting articles on unemployment. It exposed the desperate conditions that the majority of the population were having to endure.

Edith Tudor-Hart’s published work in Vienna was mostly confined to low circulation journals with a campaigning political emphasis. Neither the Communist Party in Vienna, nor the Communist Party of Great Britain, understood the value of photography in the 1930s. Both failed to produce viable magazines with much audience share.

The free exhibition Edith Tudor-Hart and Wolfgang Suschitzky is on at the Tate Britain (Pimlico tube) until 17th Nov 2019. The photography is first rate and I can really recommend a visit. I hope my background notes here will give you a greater insight into how some of the photographs came to be taken.

What remains of Edith Tudor-Hart’s archive has recently been scanned. The National Galleries of Scotland in conjunction with Wien Museum put on a well-regarded exhibition, and produced a book of of great quality reproductions called Edith Tudor-Hart In the Shadow of Tyranny.

For up-to-date information I can recommend the film “Tracking Edith” which you can pay £5.50 to stream on Vimeo.

Alan Tucker

Jenny – how fascinating. Thanks for writing in.

Mr Alfred Smith was my Grandfather (the unemployed story), i will check my loft for things put away as i know i have a book (not the magazine itself) bought from picture post years later with all those photographs in. So sorry i missed this exhibition. He went on to have 1 more child a girl, of the total 5 only 2 still with us.

Thanks Kevan!

Well, if the photographic exhibition is half as good as this article, I know where I am off to in the coming weeks. Thanks for a brilliant piece of journalism.

Kevan