This is the story of a daring 1960s cash van raid. The van was delivering to the gas works on Bow Common Lane.

Bow Common Gas Works

A short history of Gas

In 1807 Frederick Winsor installed gas lighting along Pall Mall as a demonstration. He won permission to build a gas works and run gas under the streets in pipes. Within 15 years every large town had a gas works. It was used to light public buildings, shops and factories. It wasn’t until the late 19th century that households could afford to install it. The gas mantle was invented in 1885 by Carl Auer. It gave a much brighter light. Gas cookers and geysers (for hot water) didn’t become popular until after WW1.

Until the 1970s gas was manufactured by heating coal, purifying the gas it gave off, and storing it in gas holders. Natural gas wasn’t discovered under the North Sea until 1967.

Bow Common Gas Works

The works were built in 1850 between the back of Tower Hamlets Cemetery and Bow Common Lane. The coal came in by train. The exotically named Gas Factory Junction appeared on old maps.

Bow Common Gas Works were taken over by the Gas Light and Coke Company in 1870. They spent money upgrading the works, taking the number of gas holders up to four and building the offices which you can still see on Bow Common Lane. The site was modernised again in 1926, then closed in 1968. A number of small businesses have since occupied the site.

Redevelopment is given the go ahead

The former gas works site is now being redeveloped by St William which is a joint venture between the Berkeley Group and National Grid. They specialise in the redevelopment of redundant gasworks sites. 1,450 new homes (35% affordable) are planned along with a 6th form college. The former gasworks office and laboratory building will be restored, becoming a retail and workspace hub. The Tower Hamlets planning application is here.

Architects Studio Egret West supplied the artist’s impression of the site.

Austerity and hard times after Hitler’s defeat

My father fought in the army throughout WW2. A whole generation of strong fit men were taught hand to hand combat, using explosives and guns. Conscription continued for healthy males aged 17-21 until 1960. Most, like my father, took whatever work they could back on civvy street.

People struggled through hard times. One in three houses had been destroyed, along with many factories and shops. Since the economy was surviving on American loans manufactured items were exported to earn money. They were not available for the home population. Rationing and food shortages continued, paving the way for a thriving black market. (Black as in night – you can’t see it).

On Fridays my father came home with his wages in a special brown packet. If the family needed extra money, say for a holiday, he would work overtime on Saturdays and Sundays. Getting into debt or having a bank account was quite unusual. Electricity and gas were purchased in advance by feeding coins into a meter.

But there was a small group of men watching huge amounts of untraceable used banknotes and coins being delivered to post offices and factories. Freddie Forman was one, and it was his firm (gang) that struck the cash van delivering the weeks wages to Bow Common Gas Works.

Photo credit (Rialto Pictures / Studiocanal)

Plots for films take inspiration from the real world. The Ladykillers is a wonderful comedy about a heist.

Freddie Forman – a short biography

Freddie Foreman said: “I was born in Sheepcote Lane on Saturday 5 March 1932. Every part of London has one street where villains came from, and in our area it was Sheepcote Lane…

“Number 22 Sheepcoat Lane was a terraced house, two-up and two-down. You stepped from the street straight into the front room… We five brothers shared one bedroom.”

Sheepcote Lane looks very nice now. You’d never guess it’s history from looking at it.

Foreman remembers a lot of drunkeness and fighting, including by his father. Of his grandmother he said: “She was a real scrapper, and would regularly fight with her neighbours on Saturday nights after leaving the Flag pub.”

In 1939 the house in Sheepcote lane was pulled down and the family moved into a brand new flat in Wandsworth. It had electricity and a bathroom. Then the bombing started.

In 1939 he was evacuated for the first of four times. Each time he returned to London to be with his own family he had a lucky escape from being killed by bombs.

His four brothers were away fighting in the forces but would come home to give him presents of German bayonets and Lugers, daggers, knuckle-dusters and more.

He left school at 14 after a very disrupted education. Job opportunities were limited. One of his older brothers, George, won six campaign stars and medals for risking his life fighting in the Navy. Not long after being discharged he was shovelling coal off barges in the Thames onto a conveyor belt feeding Nine Elms power station. A terrible job, breathing in coal dust.

At that time Freddie Forman was still at school, scavenging timber and cutting it up to (try to) sell as firewood. Once at work older workers educated him in the ways of syphoning off goods to sell. From that, aged 18, he graduated into working for the Forty Thieves, a famous gang of female shoplifters.

Along the the way he met Charlie Kray who would take stolen goods off his hands for cash and hide them in a lock-up on Old Ford Road. “Charlie was a good man to do business with, and safe.” Freddie Forman wrote a number of books detailing his exploits. I’m quoting from his autobiography, “The Godfather of British Crime”, which you’ll find secondhand on abebooks and on Kindle. He later worked as the twins enforcer, but robbery for big prizes was his chosen career.

Jack “the Hat” McVitie was murdered by Reggie Kray, but Forman was jailed for 10 years for disposing of the body in 1969. In the 1960s Forman was acquitted of the murders of Frank “Mad Axeman” Mitchell, and Tommy “Ginger” Marks. But in his 1969 autobiography “Respect” he admitted to them.

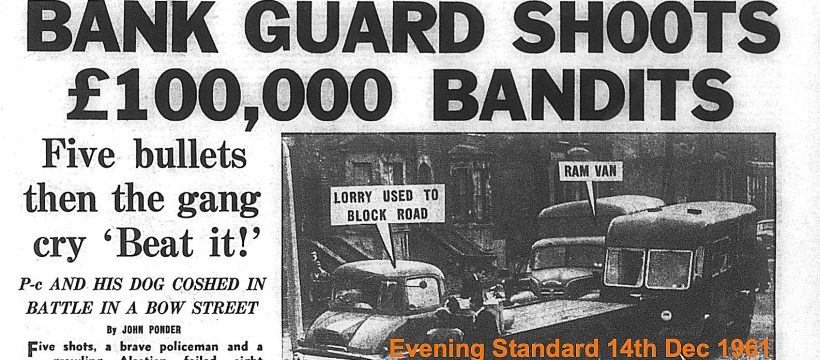

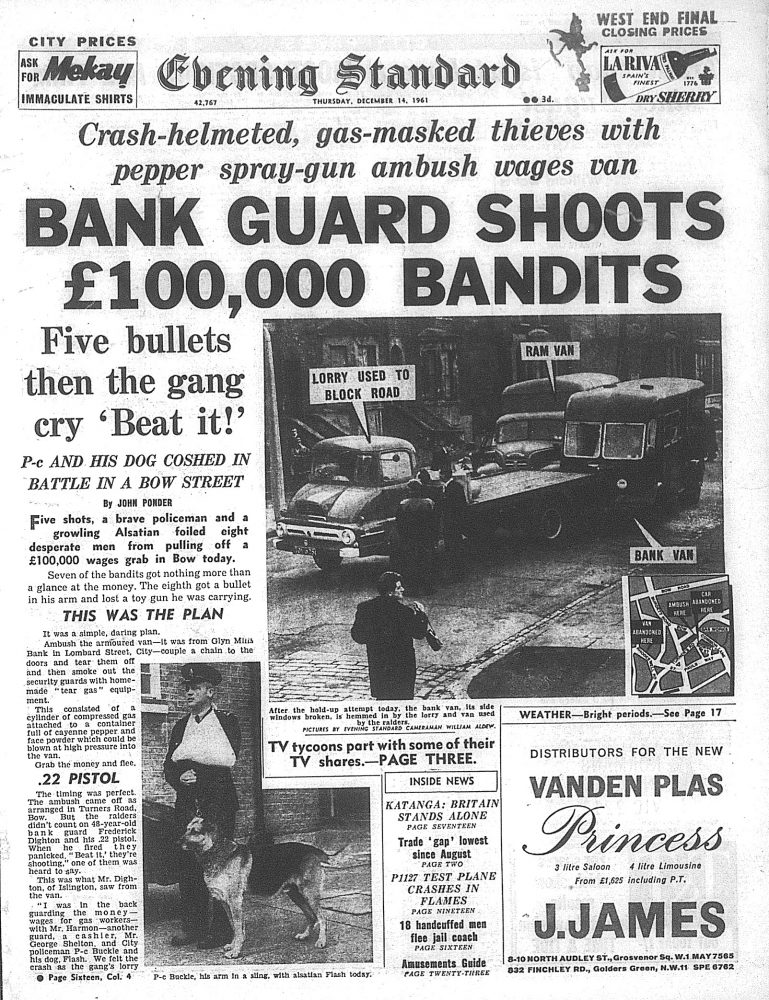

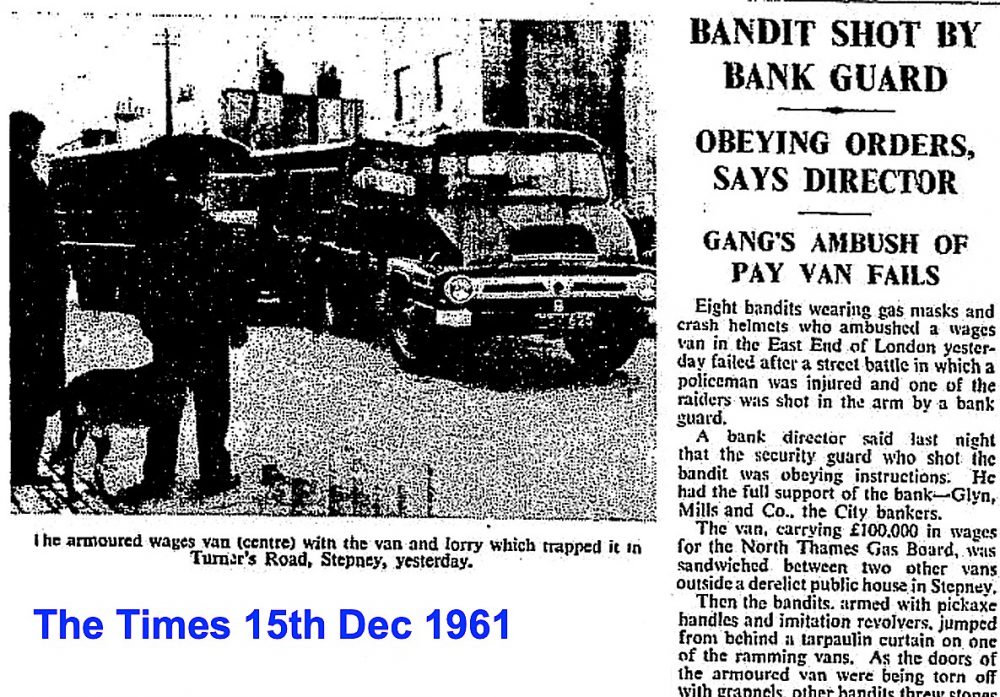

The Battle of Bow 14th December 1961

The Bow heist had been researched and planned for months. It wasn’t exactly their first job. In his autobiography Freddie Foreman said, “The target bullion van had been hired by the city bank of Glyn Mills to deliver large sums of money from their head office in Lombard Street to the East End. This was a regular trip… Their first drop was in Wapping High Street, then on to Bow, to the gasworks.” They knew who was on the van, including a City of London police constable and his dog. What came as a surprise was that the two bank clerks in the back of the van were armed!

The ambush was in Turner’s Road, now called Ackroyd Drive, opposite the gas works offices. At 9.45am as the cash van approached the offices a gang lorry which had been driving in front of it stopped suddenly and reversed hard into it. A long lorry with the side cut out of it which had been covered by a sheet of tarpaulin cashed into and scraped along the side of the cash van. The robbers in the lorry broke the windows on the side of the cash van with crowbars, causing total confusion for the guards inside. They had a copper tube and funnel connected to an oxyacetylene cylinder which was planned to blast pepper and talcum powder into the back of the van. But the driver had misjudged the crash and it didn’t line up with the window. It would have temporarily blinded all the guards.

A stolen Evening Standard delivery van had been strengthen with an iron rail across the back. Here’s what Freddie Foreman said,”At the same time, the robbers in the print van reversed against the two rear doors, smashed the back windows and passed an iron hook and chain through them. On securing the chain, the signal to drive forward was given. The print van revved up and lurched forward, wrenching off the two back doors of the target van.”

The Evening Standard article has this quote from bank guard Frederick Dighton: “I was in the back guarding the money – wages for the gas workers – with Mr. Harmon – another guard, a cashier, Mr George Shelton and City policeman P-c Buckle and his dog, Flash. We felt the crash as the gang’s lorry backed into the front of our van.

“There was another crash as a second van ran into the side of ours. Then a terrific tearing noise as the doors of our van were torn away by the heavy chain.

“Suddenly the doors were gone and there was a man with a 14lb. sledgehammer facing me. There were others behind him. Their faces were covered with gas masks. They all wore crash helmets. I had my revolver in my hand.

“I fired five times and saw one man run for the gang’s van holding his arm.”

The Evening Standard article was published on the same day as the robbery. They did really well with their speedy reporting. Having the exact date enabled me to go along to the British Library on the Euston Road to discover and read the article.

Here’s Freddie Foreman again: “The doors fell open in midair and exposed the money from the tellers in those big red-leather cricket bags [one bag for each gas works they were delivering to]… It would have been a good bit of work. But there was a city copper, Ted Buckle, and his dog Flash, who jumped out onto the street.

“One of our firm was shot through the head. Two guards shot through the windows, but we had no guns; they had the shooters. An MP later got up in Parliament and asked how many of these vans were driving around London with armed guards: ‘Is this New York or Chicago?’

“It turned out that the two guards from Coutts, the Queen’s bank, went for target practice every week.”

“Alf Gerard and I tried to climb in the back but, once they started shooting, one of our firm was crawling on his hands and knees with a bullet wound that went into his head at the base of the skull and out the other side.” They got him into the print van. Not revealed was that this was the second robber who was injured and he later died. His death could not be acknowledged. His disappearance was covered up with a story that he had run off with a mistress to Australia.

The man who wounded the bandit is Mr Frederick Dighton, aged 48, a bank security guard and a former Army sergeant. As he fired, after a guard had warned the attackers to stand off, one of them cried out “——, they’ve got guns!” and they ran away.

The Times 15th Dec 1961

Freddie Forman: “‘Are we all ’ere?’ ‘No, where’s Bill and ‘Jerry?’

“We looked down the side of the bank van to our long-backed lorry. Twenty-five yards further down the road there’s Billy Ambrose and Jerry Callaghan fighting with the copper. Jerry’s swinging on his arm and Bill’s got the dog hanging on his arsehole. The three of them were fighting in the road.

“I grabbed a stick and … ran down the side of the van. They’re further down the road now, the three of them struggling and spinning around, the dog still hanging on his arse. I’ve whacked the dog and he’s legged it. I said to the copper, ‘Let ‘em go!’ He’s got one under his arm – he was a big strong bastard, you’ve got to give him credit. He’s got hold of another stick and Jerry’s swinging on it.

“‘You bastard! You bastard!’ the copper’s saying to me.

“‘Let ‘em fucking go!’

“Whack! I gave him another and another. He let them go.

“There was a big scream about the Battle of Bow… It was a big one for that time. We’d have got the prize if not for the guns used by the bank tellers.”

As far as I can discover nobody was jailed over the Battle of Bow.

Security Express Robbery Easter 1983

The robbery at the Security Express vault in Curtain Road was Britains biggest cash robbery at the time, bigger than the Great Train Robbery of 1963. £4 million of the £6 million stolen was never recovered. In 1983 you good buy a good condition terraced house in Bow for £60k. So maybe they’d stolen the equivalent of £72 million today.

The team was put together by John Knight. I can recommend the book called Gotcha! Investigative journalist, Pete Sawyer, interviewed many people. Ronnie Knight, John Knight and Detective Inspector Peter Wilson of the Metropolitan Police are listed as co-authors.

Gotcha pieces together the complex story of how the security guards were captured and held at gunpoint, and how the gang navigated a complex alarm system. They then loaded their own van with 5 tons of used (untraceable) banknotes and were stacking them in a rented barn at Waltham Abbey three hours before the alarm was raised on Easter Monday 4th April 1983.

It took detectives a year to even begin to hear suggestions as to who might be behind it.

Freddie Forman and others fled the country to Spain immediately after the robbery. Despite trying not to flash the cash they were discovered to have mysteriously acquired lots of money.

In 1978 the extradition treaty between the UK and Spain expired. It was renewed in 1985 but the Spanish constitution prohibits retrospective laws. The British fugitives living it up in the sun on the “Costa del Crime” were still safe.

In 1988 British and Spanish police held a meeting in Madrid about improving information sharing. At the end of the meeting the senior Spanish officer said to his British equivalent: “Tell me, Cliff [Craig]. Out of all the British criminals living on the Costa del Sol, which one would you like back the most?” The answer was: “Freddie Forman”.

The next day Freddie Forman was grabbed by Spanish police, sedated, and taken on a plane to Heathrow. In April 1990 Forman was cleared of robbery at the Security Express vault, but convicted for 9 years for handling stolen cash.

Alan Tucker